August 3, 2022

This tutorial is aimed at people who learn Rake for the first time, but it is also useful for those who are already familiar with Rake. The feature of this tutorial is:

When you finish this tutorial, you’ll get the basic knowledge on Rake and apply Rake for various development.

The example source codes in this tutorial are located at a GitHub repository Rake tutorial for beginners en. Download it so that you can try the examples without typing.

The paragraph that starts with the symbol [R] is a bit high level topic for advanced Ruby users. Advanced basically refers to “a level where you can write a class”. Other users should skip this part.

The last section may be difficult for beginners. But first 4 sections are enough to write a Rakefile. So, read them first and practice writing your Rakefiles. The experience gives you deeper understanding. Then, read the rest of the tutorial. You would understand them thanks to your practice experience.

Rake is a Ruby application. For Ruby installation, refer to Ruby’s official website. Rake is a Ruby’s standard library, so it is usually included in the downloaded Ruby. But if not,

gem install rake from the command line.The GitHub repository of this documenti is here. Click “Code” button (green button) and choose “Download ZIP”. You can also clone the repository with git.

Rake is a ruby application that implements the same functions as Make.

Make is a program developed to control the entire compilation process when compiling in C. But Make can control not only C, but also various compilers and translators (programs that convert from one format to another). Make is convenient, but its syntax is complicated. It’s easy when you using it for the first time, but the more you use it, the more difficult it becomes. For example, the following is a part of a Makefile for C compiler.

application: $(OBJS)

$(CC) -o $(@F) $(OBJS) $(LIBS)

$(OBJS): %.o: %.c $(HEADER)

$(CC) -fPIC -c -o $(@F) $(CFLAGS) $<On the other hand, Rake is:

Reference:

First, the important point is to know the command rake

and the file Rakefile placed in the current directory. The

rake command takes a task name (tasks are explained later)

as an argument.

$ rake helloIn this example the argument hello is the task name.

rake will then do the following in order:

When you use Rake, your main work is writing task definitions in your Rakefile. The task called from the command line must be defined in the Rakefile.

[R] “Define/Declare a task” are used in the Rake documentation. It actually means “create an instance of the Task class” in terms of Ruby syntax.

A task is an object that has a name, prerequisites, and an action. Prerequisites and an action are optional.

The first example below has only a name.

task :simple_taskThe first element task looks like a command to

define (or declare) a task.

In general, a command in a programming language tells the

computer to do something. For example, in Bash, cd” is the

command to change the current directory. When you type

cd /var in your command line, it moves the current

directory to /var. It is the result of execution of the

cd command with the /var argument.

Similarly, the task command is given the argument

:simple_task. And executing the task command creates a task

with the name “simple_task”. The argument :simple_task is a

symbol, but you can also use a string like this:

task "simple_task"Both lines create the same task.

On the other hand, the task command is actually a Ruby

method in terms of Ruby syntax. And :simple_task is an

argument to the method. From now on, a task may be called a

command or methods.

I think it won’t make any confusion and no worrying is necessary.

[R] From Ruby’s syntax, the

taskcommand is a “method call”, and:simple_taskis an argument to the method. In Ruby, you can write arguments with or without parentheses so the example above is a correct ruby program. If you use parentheses,task("simple_task")Be careful that there’s no blank between the method and the left parenthesis.

You can define it either way, but it’s better to leave out parentheses.

“Defining a task” means “creating an instance of the Task class”. An instance is usually created with the class’s

newmethod. But it is not the only way to create an instance. Thetaskmethod callsTask.newin its body so that the method can create an instance. In addition, thetaskmethod is more convenient thannewmethod.

Task simple_task has no prerequisites and actions.

Let’s run the task from the command line. If you haven’t download the repository, do it now.

It is assumed that the current directory is the top directory of the

downloaded and unzipped data. Change your current directory to

example/example1.

$ ls

Rakefile Rakefile2 Rakefile3 Rakefile4

$ cat Rakefile

task :simple_task

$ rake simple_taskThe task simple_task is called in the last line. Since

it has no action, nothing happens. Check whether the task is

defined.

$ rake -AT

rake simple_task #Option -AT displays all registered tasks. Now you know

that “simple_task” is defined.

Actions are represented by a block of the task method.

task: hello do

print "Hello world!\n"

endThis task is named hello. It has no prerequisites. The

action is to display “Hello world!” on the screen.

The task command above is written in Rakefile2, not

Rakefile. So, it is necessary to give rake the filename

Rakefile2 as a rakefile. To do this, -f option

is used.

$ cat Rakefile2

task: hello do

print "Hello world!\n"

end

$ rake -f Rakefile2 hello

Hello world!The task hello is invoked and its action is executed. As a result, the string “Hello world!” is displayed.

[R] Ruby has two ways of representing blocks: (1) curly braces (

{and}) and (2)doandend. Both will work in a Rakefile, but it’s better to usedoandendfor readability. Also, if you use curly braces like this, it won’t work:task :hello {print "Hello world!\n"}This causes an error because curly braces bind more tightly to the preceding expression than do-ends. So, Ruby recognaizes that

:helloand the curly brace are a syntactic group to parse. Therefore, the curly braces aren’t seen a block for the ‘task’ method. Please see Ruby FAQ for further information. To fix this, put parentheses around the argument.task(:hello) {print "Hello world!\n"}In Rakefile, it is good to write a

taskas if it were a command. Therefore, writing a task command with parentheses is NOT recommended.Thanks to Ruby’s flexible syntax such as omitting parentheses in arguments, Ruby can make methods look like commands. And you can make a new language for a specific purpose. Such language is called “DSL (Domain-Specific Language)”. The idea that Rake is a kind of DSL, brings the do-end recommendation.

If a task has prerequistes, it calls them before its action is invoked.

A task definition with prerequisites is like this:

task task name => [ a list of prerequisites ] do

action

endtask name => [ a list of prerequisites ] is a Ruby

hash. You can leave out the braces ({ and })

when the hash is the last argument of the method call. If you do not

omit it, it will be

{ task name => [ a list of prerequisites ] }. It also

works.

If the task name is a symbol, you can write abc: "def"

instead of :abc => "def". Similarly,

:abc => :def and abc: :def are the

same.

There are two tasks in the following example. Their names are “first” and “second”. “First” is a prerequisite for “second”.

task second: :first do

print "Second.\n"

end

task: first do

print "First.\n"

endWhen you call the task “second”, the prerequisite “first” is invoked before the execution of “second”.

invoke first => execute secondNow, run rake.

$ rake -f Rakefile3 second

First.

Second.Utagawa-san’s Write a recipe for ajitama in a Makefile was so interesting that I made its Rake version.

# Make a "ajitama" (flavored egg)

task :Boil_hot_water do

print "Boil water.\n"

end

task Boil_eggs: :Boil_hot_water do

print "Boil eggs.\n"

end

task :Wait_8_minutes => :Boil_eggs do

print "Wait 8 minutes.\n"

end

task Add_ice_into_the_bowl: :Wait_8_minutes do

print "Add ice to the bowl.\n"

end

task Fill_water_in_bowl: :Add_ice_into_the_bowl do

print "Fill the bowl with water.\n"

end

task Put_the_eggs_in_the_bowl: :Fill_water_in_bowl do

print "Put the eggs into the bowl.\n"

end

task Shell_the_eggs: :Put_the_eggs_in_the_bowl do

print "Shell the eggs.\n"

end

task :Write_the_date_on_the_ziplock do

print "Write the date on the ziplock.\n"

end

task Put_mentsuyu_into_a_ziplock: [:Write_the_date_on_the_ziplock, :Shell_the_eggs] do

print "Put mentsuyu (Japanese soup base) into a ziplock.\n"

end

task Put_the_eggs_in_a_ziplock: :Put_mentsuyu_into_a_ziplock do

print "Put eggs in a ziplock.\n"

end

task Keep_it_in_the_fridge_one_night: :Put_the_eggs_in_a_ziplock do

print "Keep it in the fridge one night.\n"

end

task Ajitama: :Keep_it_in_the_fridge_one_night do

print "Ajitama is ready.\n"

endNow run rake.

$ rake -f Rakefile4 Ajitama

Write the date on the ziplock.

Boil water.

Boil eggs.

Wait 8 minutes.

Add ice to the bowl.

Fill the bowl with water.

Put the eggs into the bowl.

Shell the eggs.

Put mentsuyu (Japanese soup base) into a ziplock.

Put eggs in a ziplock.

Keep it in the fridge one night.

Ajitama is ready.Tasks that have already been invoked doesn’t invoke their actions. In other words, tasks are invoked only once.

For example, if you change the ajitama’s Rakefile like this:

from:

task Put_the_eggs_in_a_ziplock: :Put_mentsuyu_into_a_ziplock doto:

task Put_the_eggs_in_a_ziplock: [:Put_mentsuyu_into_a_ziplock, :Shell_the_eggs] doThen, :Shell_the_eggs is a prerequisite in two different

tasks. So, It is invoked twice, but the second invocation is ignored.

And the result is the same as before.

[R] The Task class has two instance methods “invoke” and “execute”. “Invoke” performs the action only once, while “execute” performs it as many times as the method is called. So, Rake documentation distinguishes the two words “call” and “execute”. I use the two words without exact distinction in this tutorial. Though there may exist some ambiguous parts in this tutorial, I don’t think they bring any big confusion. Note that “invoke” calls the prerequisites before performing its own task, but “execute” does not call the prerequisites.

We’ve used symbols in task names, but you can also use strings.

task "simple_task"

task "second" => "first"It is possible to write it like this. To describe a hash with a symbol, you can write something like “{abc: :def}”, but you can’t use this if the symbol starts with a number. “{0abc: :def}” and “{abc: :2def}” causes syntax errors. It must be written like “{:‘0abc’ => :def}” and “{abc: :‘2def’}”. If you use strings, no such problem happens.

The following format is often used.

task abc: %w[def ghi]%w returns an array of strings separated by spaces.

%w[def ghi] and ["def", "ghi"] are the same.

Please refer to The

Ruby Programming Wikibook.

If you use % notation in Ajitama Rakefile, it will be like this:

task Put_mentsuyu_into_a_ziplock: %w[Write_the_date_on_the_ziplock Shell_the_eggs] doFile tasks are the most important tasks in Rake.

A file task is a task but its name is a filename. A file task has a “name”, “prerequisites” and an “action” like a general task. There are three differences from general tasks:

Except for the things above, file tasks behave like general tasks. For example, they invoke prerequisites before executing their action and they invoke their action only once.

File task has two conditions. If the conditions below hold, the action will be invoked.

[R] The mtime (last modified time) here is the value of

File.mtimemethod. Linux files have three timestamps: atime, mtime and ctime.

- atime: last access time

- mtime: last modified time

- ctime: last inode change time

File.mtimemethod returns the mtime above. (The original Ruby written in C language gets its value with a C function.)

I’d like to show you a simple example. It is to create a backup file

“a.bak” for the text file “a.txt”. The easiest way is to use

cp command.

$ cp a.txt a.bakBut I’d like to show you a Rakefile which performs the same thing.

file "a.bak" => "a.txt" do

cp "a.txt", "a.bak"

endThe contents of this Rakefile are:

file method defines a file task “a.bak”cp "a.txt", "a.bak".The cp method copies the first argument file to the

second argument file. This method is defined in the FileUtils module.

FileUtils is a standard Ruby library, but it’s not built-in, so you

usually have to write require 'fileutils' in your program.

But you don’t need to write it in your Rakefile as Rake automatically

requires it.

When the task “a.bak” is called, the prerequisite “a.txt” is called before the execution of “a.bak”. However, the definition of the task “a.txt” is not written in the Rakefile. How does Rake behave when there are no task definitions? Rake defines a file task “a.txt” as a name-only task (no prerequisites and no action) if the file “a.txt” exists. Then it calls that task, but since it has no action, nothing happens and it returns to “a.bak”. If “a.txt” does not exist, an error will occur.

Now let’s run rake. Move your current directory to

example/example2 and type as follows.

$ rake -f Rakefile1 a.bak

cp a.txt a.bak

$ diff a.bak a.txt

$ rake a.bak

$I’d like to show you how to backup multiple files in this subsection. Create new files “b.txt” and “c.txt” in advance. The simplest Rakefile would be something like this:

file "a.bak" => "a.txt" do

cp "a.txt", "a.bak"

end

file "b.bak" => "b.txt" do

cp "b.txt", "b.bak"

end

file "c.bak" => "c.txt" do

cp "c.txt", "c.bak"

endThere are three file tasks defined here. Delete “a.bak” and run rake like this:

$ rm a.bak

$ rake -f Rakefile2 a.bak

cp a.txt a.bak

$ rake -f Rakefile2 b.bak

cp b.txt b.bak

$ rake -f Rakefile2 c.bak

cp c.txt c.bak

$ ls | grep .bak

a.bak

b.bak

c.bakMaybe you would say:

“If I were you, I wouldn’t do this. Using rake three times is the same as using cp three times.”

You are right. I don’t want to run rake three times, too. I want to run rake once and copy all 3 files. This can be achieved by associating a general task with three file tasks. Let’s start by creating a “copy” task, which has the three file tasks as its prerequisites.

task copy: %w[a.bak b.bak c.bak]

file "a.bak" => "a.txt" do

cp "a.txt", "a.bak"

end

file "b.bak" => "b.txt" do

cp "b.txt", "b.bak"

end

file "c.bak" => "c.txt" do

cp "c.txt", "c.bak"

endRun Rake.

$ rm *.bak

$ rake -f Rakefile3 copy

cp a.txt a.bak

cp b.txt b.bak

cp c.txt c.bakI got 3 backup files at once.

Now restructure the Rakefile. THe change includes the following two:

backup_files = %w[a.bak b.bak c.bak]

task default: backup_files

backup_files.each do |backup|

source = backup.ext(".txt")

file backup => source do

cp source, backup

end

endbackup_files.each method to get each element of the backup file

array. The element is assigned to the backup parameter of

the block.source. The ext method is

added to the String class by Rake. The original String class does not

have ext method.file command. The iterator

each repeats the block three times, so the

file command is executed three times. Then, three file

tasks “a.bak”, “b.bak” and “c.bak” will be defined.Now, Run Rake.

$ rm *.bak

$ rake -f Rakefile4

cp a.txt a.bak

cp b.txt b.bak

cp c.txt c.bak

$ touch a.txt

$rake -f Rakefile4

cp a.txt a.bak

$a.txt to update the mtime of

a.txt.a.bak is

executed because the mtime of a.txt is newer than the one

of a.bak. No other tasks are invoked because the other

backup files have newer mtime than the original files.I used touch to change the mtime, but usually mtime is

updated when the file is updated with an editor. In other words, when

the original file is updated, the file task action will be invoked.

Refactor the Rakefile a little. The following code shows how to use task instances method in blocks.

Change the file task definition to:

file backup => source do |t|

cp t.source, t.name

endThe block now has a new parameter “t”, which the file task

backup is assigned to. The backup task is an

instance of the Task class. It has convenient methods.

name returns the name of the task.prerequisites returns an array of prerequisites.sources returns a list of files that the task depends

on.source returns the first element of

sources.There are some other methods, but the four methods above are the most commonly used.

In the new file task definition, its action is to copy

t.source to t.name. They are

source and backup respectively, so the action

performs the same as before.

The same parameter (t) can be used in a block of

task methods.

Now, run Rake.

$ rm *.bak

$ rake -f Rakefile5

cp a.txt a.bak

cp b.txt b.bak

cp c.txt c.bakThe actions of the tasks were copying files with the “.txt” extension

to files with the “.bak” extension. If you apply this to the file

“a.bak”, you will get a file task with the action “copy a.txt to a.bak”.

This way how to create file tasks are called a rule. Rules can be

defined with the rule method. Let’s take a look at an

example.

backup_files = %w[a.bak b.bak c.bak]

task default: backup_files

rule '.bak' => '.txt' do |t|

cp t.source, t.name

endThe first three lines are the same as before. The third line tells

that the prerequisites of the task default are

a.bak, b.bak and c.bak. But those

tasks are not declared. In that case, rake will try to define file tasks

just before the prerequisites are invoked.

The rule in this example looks like this:

t.source (the first element in

the array of files that the task depends on) to t.name

(task name = file name).All three tasks a.bak, b.bak and

c.bak match the rule, so the tasks are defined according to

the rule. Run Rake.

$ rm *.bak

$ rake -f Rakefile6

cp a.txt a.bak

cp b.txt b.bak

cp c.txt c.bak

$It worked as before.

The “.bak” part of the rule method is converted by Rake to a regular

expression /\.bak$/. And the regular expression is compared

with the task names a.bak, b.bak and

c.bak. You can use regular expressions for the task name of

the rule instead of strings from the very first.

rule /\.bak$/ => '.txt' do |t|

cp t.source, t.name

endRun rake.

$ rm *.bak

$ rake -f Rakefile7

cp a.txt a.bak

cp b.txt b.bak

cp c.txt c.bak

$[R] Regular expression represents arbitrary patterns. So, it is possible to change the backup filename to include a tilde “~” at the beginning, such as “~a.txt”.

backup_files = %w[~a.txt ~b.txt ~c.txt] task default: backup_files rule /^~.*\.txt$/ => '.txt' do |t| cp t.source, t.name endBut this doesn’t work.

$ rake rake aborted! Rake::RuleRecursionOverflowError: Rule Recursion Too Deep: [~a.txt => ~a.txt => ~a.txt => ~a.txt => ~a.txt => ~a.txt => ~a .txt => ~a.txt => ~a.txt => ~a.txt => ~a.txt => ~a.txt => ~a.txt => ~a.txt => ~a.txt => ~a.txt => ~a.txt] Tasks: TOP => default (See full trace by running task with --trace)The

=> '.txt'part has a problem. The filename “~a.txt” matches the rule again, so rake try to apply the rule to “~a.txt”. In other words, the task name and the dependent task name are the same, so we end up in an infinite loop when applying the rule. Rake issues an error at the 16th loop.To avoid this, define the dependent file with a Proc object.

backup_files = %w[~a.txt ~b.txt ~c.txt] task default: backup_files rule /^~.*\.txt$/ => proc {|tn| tn.sub(/^~/,"")} do |t| cp t.source, t.name endThe task name (e.g. “~a.txt”) is passed by Rake as an argument to the proc method block. You can use the lambda method or “->( ){ }” instead of proc method. See Ruby documentation.

$ rm ~* $ rake -f Rakefile8 cp a.txt ~a.txt cp b.txt ~b.txt cp c.txt ~c.txt $

This section describes useful features that support file tasks. Specifically, they are “FileList”, “pathmap” and “directory task”.

FileList is an array-like object of filenames. It can be manipulated like an array of strings and has some nice features.

The [ ] class method creates a FileList instance which

has elements of files given with the arguments. The arguments are files

separated with commas.

files = FileList["a.txt", "b.txt"]

p files

task :defaultThe variable files is assigned a FileList instance which

has “a.txt” amd “b.txt” as its elements.

If no task is defined in the Rakefile, Rake issues “Don’t know how to build task ‘default’” error. To avoid thus, a default task is defined in the fourth line.

When Rake is invoked from the command line, it behaves like this:

When the Rakefile is executed, a FileList instance is created, displayed, and the default task is defined. Note that these are done before the default task invocation.

$ rake -f Rakefile1

["a.txt", "b.txt"]

$You can also use the glob pattern commonly used in Bash.

files = FileList["*.txt"]

p files

task:defaultRun Rake.

$ rm d.txt

$ ls

Rakefile1 Rakefile4 Rakefile7 a.txt dst

Rakefile2 Rakefile5 Rakefile8 b.txt src

Rakefile3 Rakefile6 Rakefile9 c.txt '~a.txt'

$ rake -f Rakefile2

["a.txt", "b.txt", "c.txt", "~a.txt"]

$Please refer to the Ruby documentation for glob patterns.

Let’s think about the way to back up all the text files. Here, “text file” is a file with “.txt” extension. Note that “all the text files” are determined at the time rake runs, not the time you write the Rakefile. So you have to create a mechanism in the Rakefile to get text files.

files = FileList["*.txt"]When this line is executed, ruby gets files that match “*.txt”. The files include “~a.txt”. But it should be excluded since it is a backup file whose original is “a.txt”.

files = FileList["*.txt"]

files.exclude("~*.txt")

p files

task:defaultThe exclude method adds the given pattern to its own

exclusion list.

$ rake -f Rakefile3

["a.txt", "b.txt", "c.txt"]

$The file “~a.txt” is removed from the variable

files.

The variable files is now set to the file list of the

original files. They are prerequisites. For example,

In order to define a file task, it is necessary to obtain the task

name (destination filename) from the source filename. To do so, use the

ext method of FileList class. The ext method

changes the extension of all files included in the file list.

names = sources.ext(".bak")The Rakefile is like this.

sources = FileList["*.txt"]

sources.exclude("~*.txt")

names = sources.ext(".bak")

task default: names

rule ".bak" => ".txt" do |t|

cp t.source, t.name

endRun Rake.

$rake -f Rakefile4

cp a.txt a.bak

cp b.txt b.bak

cp c.txt c.bak

$Now add a text file and run Rake again.

$ echo Appended text file. >d.txt

$ rm *.bak

$ rake -f Rakefile4

cp a.txt a.bak

cp b.txt b.bak

cp c.txt c.bak

cp d.txt d.bak

$A new file “d.txt” is also copied. This means that Rakefile makes backup files of “all the text files” at the time Rake runs.

The “*.txt” file in this example is sometimes referred to as the sources and the “*.bak” files as the targets. In general, it can be said that the source exists, but the target does not necessarily exist. Therefore, source files is often get first and then the target filenames are created from the source.

The pathmap method is a powerful method for FileList.

Originally pathmap was an instance method of the String object. The

FileList’s pathmap method performs String’s pathmap for each element of

the FileList. Pathmap returns various information depending on its

arguments. Here are some examples.

In advance, create a “src” directory in the current directory and create “a.txt”, “b.txt” and “c.txt” under it.

$ mkdir src

$ touch src/a.txt src/b.txt src/c.txt

$ tree

.

├── Rakefile

├── a.bak

├── a.txt

├── b.bak

├── b.txt

├── c.bak

├── c.txt

├── d.bak

├── d.txt

├── src

│ ├── a.txt

│ ├── b.txt

│ └── c.txt

└── ~a.txt

1 directory, 14 files

$A Rakefile to test pathmap is like this:

sources = FileList["src/*.txt"]

p sources.pathmap("%p")

p sources.pathmap("%f")

p sources.pathmap("%n")

p sources.pathmap("%d")

task:defaultThe variable sources contains “src/a.txt”, “src/b.txt”

and “src/c.txt”. Run Rake.

$ rake -f Rakefile5

["src/a.txt", "src/b.txt", "src/c.txt"]

["a.txt", "b.txt", "c.txt"]

["a", "b", "c"]

["src", "src", "src"]The pathmap method allows you to specify a pattern and its replacement delimited by a comma and enclose them in curly braces. The replacement specification is placed between the % and the directive. For example, “%{src,dst}p” returns the pathname with “src” replaced by “dst”. This can be used to get the “task name” from the “dependent file name”.

The following Rakefile copies all text files under the src directory to the dst directory.

sources = FileList["src/*.txt"]

names = sources.pathmap("%{src,dst}p")

task default: names

mkdir "dst" unless Dir.exist?("dst")

names.each do |name|

source = name.pathmap("%{dst,src}p")

file name => source do |t|

cp t.source, t.name

end

endThe second line uses the pathmap replacement

specification.

sources is an array

["src/a.txt", "src/b.txt", "src/c.txt"]names will be an array

["dst/a.txt", "dst/b.txt", "dst/c.txt"]Line 6 creates the destination directory “dst” if it does not exist.

The mkdir method is defined in the FileUtils module, which

Rake automatically requires. Line 8 uses the string pathmap method to

get the dependency filename from the task name.

name is dst/a.txt, dst/b.txt

or dst/c.txtsource will be src/a.txt,

src/b.txt or src/c.txtRun Rake

$ rm -rf dst

$ rake -f Rakefile6

mkdir dst

cp src/a.txt dst/a.txt

cp src/b.txt dst/b.txt

cp src/c.txt dst/c.txt

$[R] You can also use a rule that uses a regular expression and Proc object.

sources = FileList["src/*.txt"] names = sources.pathmap("%{src,dst}p") task default: names mkdir "dst" unless Dir.exist?("dst") rule /^dst\/.*\.txt$/ => proc {|tn| tn.pathmap("%{dst,src}p")} do |t| cp t.source, t.name endRun Rake

$ rm dst/* $ rake -f Rakefile7 cp src/a.txt dst/a.txt cp src/b.txt dst/b.txt cp src/c.txt dst/c.txt $Using a rule is simpler than an iterator.

The directory method creates a directory task. A

directory task creates a directory with the task name if it does not

exist.

directory "a/b/c"This directory task creates a directory “a/b/c”. If the parent directories “b” and “a” don’t exist, create them too.

You can also use this to create the “dst” directory.

sources = FileList["src/*.txt"]

names = sources.pathmap("%{src,dst}p")

task default: names

directory "dst"

names.each do |name|

source = name.pathmap("%{dst,src}p")

file name => [source, "dst"] do |t|

cp t.source, t.name

end

endNote that directory tasks are “tasks”, so they are just defined

during the Rakefile are executed. The tasks need to be invoked by

another task. So, add dst to the prerequisite for

dst/a.txt, dst/b.txt and

dst/c.txt. This makes the directory before copying.

Run Rake

$ rm dst/*

$ rake -f Rakefile8

cp src/a.txt dst/a.txt

cp src/b.txt dst/b.txt

cp src/c.txt dst/c.txt

$[R] Rewrite the Rakefile with a rule.

sources = FileList["src/*.txt"] names = sources.pathmap("%{src,dst}p") task default: names directory "dst" rule /^dst\/.*\.txt$/ => [proc {|tn| tn.pathmap("%{dst,src}p")}, "dst"] do |t| cp t.source, t.name endA directory task has been added to the rule’s prerequisites.

In this subsection we will combine Pandoc and Rake to create an HTML file. Clean and Clobber will be also explained.

Pandoc is an application that converts among lots of document formats. For example,

Many other document formats are also supported. For further information, see the Pandoc website.

Pandoc is executed from the command line.

pandoc -o destination_file source_fileThe option -o tells a destination file to pandoc. Pandoc

determines the file format from the extensions both source and

destination.

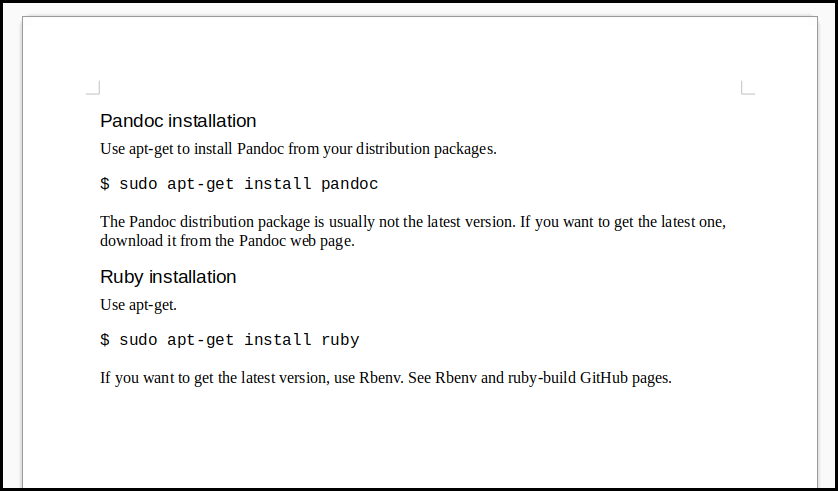

In the following example, a word file example.docx is

converted into an HTML file. The word file looks like this:

Now convert it into an HTML file. Pandoc is executed with

-s option, which I will explain later.

$ pandoc -so example.html example.docxThis will create a file example.html. Double-click to

display it in a browser.

The contents are the same as the one in the Word file. The HTML source code is as follows.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1999/xhtml" lang="" xml:lang="">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8" />

<meta name="generator" content="pandoc" />

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0, user-scalable=yes" />

<title>example</title>

... ... ...

... ... ...

</head>

<body>

<h1 id="pandoc-installation">Pandoc installation</h1>

<p>Use apt-get to install Pandoc from your distribution packages.</p>

<p>$ sudo apt-get install pandoc</p>

<p>The Pandoc distribution package is usually not the latest version. If

you want to get the latest one, download it from the Pandoc web

page.</p>

<h1 id="ruby-installation">Ruby installation</h1>

<p>Use apt-get.</p>

<p>$ sudo apt-get install ruby</p>

<p>If you want to get the latest version, use Rbenv. See Rbenv and

ruby-build GitHub pages.</p>

</body>

</html>One important thing is that a header has been added. This is because

you gave pandoc the -s option. Without -s,

only the part between the body tags is generated.

This section describes how to convert markdown to HTML and automate the work with Rake.

Assume all source files are in the current directory. (“Current

directory” is example/example4). The generated HTML will be

created in the docs directory. The markdown files are

“sec1.md”, “sec2.md”, “sec3.md” and “sec4.md”.

In Pandoc markdown, we write metadata with % first. This represents the title, author and date.

% Rake tutorial for beginners

% ToshioCP

% August 5, 2022The title will be put in the title tag in the HTML

header.

PC screen width is usually too big to read a document so it is appropriate to put a CSS to make the width shorter.

body {

padding-right: 0.75rem;

padding-left: 0.75rem;

margin-right: auto;

margin-left: auto;

}

@media (min-width: 576px) {

body {

max-width: 540px;

}

}

@media (min-width: 768px) {

body {

max-width: 720px;

}

}

@media (min-width: 992px) {

body {

max-width: 960px;

}

}

@media (min-width: 1200px) {

body {

max-width: 1140px;

}

}

@media (min-width: 1400px) {

body {

max-width: 1320px;

}

}This CSS has been written while referencing the Bootstrap’s container class.

This CSS adjusts the width of body according to the

screen size. It’s a technique called responsive web design (RWD). You

can get more information if you search for “responsive web design” in

the internet.

Save this as style.css in the top directory, where you

put your Rakefile. The option -c style.css makes pandoc

include the stylesheet file in the header of the HTML.

A Rakefile creates an HTML from the four files “sec1.md” to

“sec4.md”. The target HTML and “style.css” will be located under

docs directory.

There are two possible ways.

Both have advantages and disadvantages. This tutorial takes the second way because it’s easier than the first.

sources = FileList["sec*.md"]

task default: %w[docs/LearningRake.html docs/style.css]

file "docs/LearningRake.html" => %w[LearningRake.md docs] do |t|

sh "pandoc -s --toc -c style.css -o #{t.name} #{t.source}"

end

file "LearningRake.md" => sources do |t|

lerning_rake = t.sources.inject("") {|s1, s2| s1 << File.read(s2) + "\n\n"}

File.write("LearningRake.md", lerning_rake)

end

file "docs/style.css" => %w[style.css docs] do |t|

cp t.source, t.name

end

directory "docs"Task relationships are a bit complicated. Let’s look at them one by one.

default are

docs/LearningRake.html and

docs/style.css.docs/LearningRake.html depends on

LearningRake.md and a directory docs.LearningRake.md depends on 4 files

(sec1.md to sec4.md).docs/style.css depends on style.css and

the directory docs.docs is a directory task, defined with the directory

method.The sh method is in line 6. It is similar to Ruby’s

system method and executes the argument as an external

command. It invokes Pandoc via bash. The sh

method is a Rake extension to FileUtils class.

Pandoc option --toc automatically generates a table of

contents. By default, Markdown headings from # to

### will be put in the table of contents.

The inject method on line 10 is an Array instance

method. The argument (an empty string) is the initial value of

s1. The values in the array are sequentially assigned to

s2 and calculated, and the result is assigned to the next

s1. See how the method works step by step.

"" (the

argument). it is assigned to s1 in the block.s2 is assigned the first array element “sec1.md”, and

s1 << File.read(s2) + "\n" is executed. As a result,

“contents of sec1.md + newline+newline” is added to the string pointed

to by s1, and that string becomes the return value of the

<< method. The return value will be assigned to

s1 in the block when it is executed in the second time.

(The actual process is complicated, but in short, it can be said that

s1 is added with “contents of sec1.md + newline+newline”

and becomes the next s1.)s1 is replaced with

“sec1.md contents + newline+newline”, and s2 is replaced

with the next array element “sec2.md”. The block is executed, and

“sec2.md contents + newline+newline” is added to s1. As a

result, s1 becomes “contents of sec1.md + newline+newline +

content of sec2.md + newline+newline”. This will be assigned to the next

s1.s1, and the next array element

“sec3.md” is assigned to s2. Then “contents of sec3.md +

newline+newline” is added.s1 and the next array element

“sec4.md” is assigned to s2. Then “contents of sec4.md +

newline+newline” is added.lerning_rake. In

short, it will be a string that combines four files with double newlines

in between. Line 11 saves it to the file “LearningRake.md”.There are two reasons that I added two newlines to the end of the file. One is that in general “a text file may or may not end with a newline”. And the other is that a blank line is sometimes necessary before a header. If you connect the next file without newlines, the first character of the second file may not start the line. Then, it is possible that the “#” of the heading is shifted from the beginning of the line and is no longer a heading. If there’s no blank line before a header, then the header connects to the prior block. Pandoc sometimes see them as a single block and the header won’t be converted correctly. Line breaks is added to avoid this.

Change your current directory to example/example4 and

execute rake.

$ rake -f Rakefile1

mkdir -p docs

pandoc -s --toc -c style.css -o docs/LearningRake.html LearningRake.md

cp style.css docs/style.css

$Double click example/example4/docs/LearningRake.html,

then your brouwser shows the contents.

In the converting process, the file “LearningRake.md” has been created. It is an intermediate file, which may be useless once the target file is created. And it is probably appropriate that such intermediate files should be removed. The clean task performs such operations.

rake/cleanCLEAN, which is

the FileList object. There are some methods to add files to

CLEAN such as <<, append,

push, and include.clean removes all the files stored in

CLEANAnother useful FileList is CLOBBER.

CLEAN.CLOBBER.Now, the Rakefile with CLEAN and CLOBBER is

like this:

require 'rake/clean'

sources = FileList["sec*.md"]

task default: %w[docs/LearningRake.html docs/style.css]

file "LearningRake.html" => %w[LearningRake.md docs] do |t|

sh "pandoc -s --toc -c style.css -o #{t.name} #{t.source}"

end

CLEAN << "LearningRake.md"

file "LearningRake.md" => sources do |t|

learning_rake = t.sources.inject("") {|s1, s2| s1 << File.read(s2) + "\n\n"}

File.write("LearningRake.md", learning_rake)

end

file "docs/style.css" => %w[style.css docs] do |t|

cp t.source, t.name

end

directory "docs"

CLOBBER << "docs"The following instruction removes LearningRake.md.

$ rake -f Rakefile2 cleanThe following instruction removes all the generated files.

$ rake -f Rakefile2 clobberIn this section, we will create a PDF file with Pandoc and Rake. The namespaces is also explained here.

Pandoc is able to convert Markdown to PDF. There are several intermediate file formats to generate PDF files. LaTeX, ConTeXt, roff ms, and HTML are such formats.

We’ll choose LaTeX as an intermediate file format here.

Markdown => LaTeX => PDFPdfLaTeX, XeLaTeX and LuaLaTeX can be used as a LaTeX engine to convert a tex file to PDF. LuaLeTeX will be used here.

Pandoc Markdown has its own extensions from the original Markdown. One of the extensions is Metadata. It’s written at the beginning of the Markdown text and configures some information for Pandoc. They are written in YAML format. For more information about YAML, see Wikipedia or YAML official page.

% Rake tutorial for beginners

% Toshio CP

% August 5, 2022

---

document class: article

geometry: margin=2.4cm

toc: true

numbersections: true

secnumdepth: 2

---

---Metadata starting with % is the same as the one in the previous

section. They represents the title, author, and date of creation,

respectively. The part surrounded by --- lines is YAML

metadata. See the Pandoc manual for what items can be set here. The

items here are as follows.

Add the above to the beginning of “sec1.md”.

In the previous section, I used “###” to “#####” for headings in the Markdown files, but that doesn’t make it a LaTeX section or subsection, so I need to change it from “#” to “###”. Since it is troublesome to do it manually, I’ve written a Ruby program.

files = (1..4).map {|n| "sec#{n}.md"}

files.each do |file|

s = File.read(file)

s.gsub!(/^###/,"#")

s.gsub!(/^####/,"##")

s.gsub!(/^#####/,"###")

File.write(file,s)

endFile in example/example5 has already changed its ATX

headings so you don’t need to run ch_head.rb.

We need to change one more. Sec2.md has a long line in a fence code block. It will overflow in the PDF.

> $ rake

> rake aborted!

> Rake::RuleRecursionOverflowError: Rule Recursion Too Deep: ... ... ...

The long line is devided into three lines like this:

> $ rake

> rake aborted!

> Rake::RuleRecursionOverflowError: Rule Recursion Too Deep: [~a.txt => ~a.txt =>

> ~a.txt => ~a.txt => ~a.txt => ~a.txt => ~a .txt => ~a.txt => ~a.txt => ~a.txt =>

> ~a.txt => ~a.txt => ~a.txt => ~a.txt => ~a.txt => ~a.txt => ~a.txt]We start with the previous Rakefile and modify it. It is easier than writing it from scratch.

require 'rake/clean'

sources = FileList["sec*.md"]

task default: %w[LearningRake.pdf]

file "LearningRake.pdf" => "LearningRake.md" do |t|

sh "pandoc -s --pdf-engine lualatex -o #{t.name} #{t.source}"

end

CLEAN << "LearningRake.md"

file "LearningRake.md" => sources do |t|

learning_rake = t.sources.inject("") {|s1, s2| s1 << File.read(s2) + "\n\n"}

File.write("LearningRake.md", learning_rake)

end

CLOBBER << "LearningRake.pdf"Change your current directory to example/example5 and

run Rake.

$ rake

pandoc -s --pdf-engine lualatex -o Beginning Rake.pdf Beginning Rake.md

$It takes a little longer than before (about 10 seconds).

HTML is suitable for publishing on the web, and PDF is suitable for viewing at hand. In the next subsection, we’ll combine these two tasks into a single Rakefile.

Now we combine two tasks (HTML and PDF) into one Rakefile. Namespaces is used here to make the Rakefile organized.

Namespaces are a common technique when building large programs, and are not limited to Rake. Here, we define two namespaces like this:

A namespace is declared with namespace method.

namespace namespace_name do

Task definition

・・・・

endIn the previous Rakefile, each work was started with the default

task. In the new Rakefile, we will make a build task for

each. Since the build task is defined under the namespace,

they are:

In this way, tasks under a namespace are represented by connecting them with a colon, such as “namespace_name: task_name”.

Namespaces only apply to general tasks (not file or directory tasks). A file task is a filename, and the filename doesn’t change even if it’s defined in a namespace. Namespaces are not used when referencing file tasks, too.

Some preparations are required to combine two tasks into one Rakefile.

? is a number from 1 to 7.The metadata files are as follows.

metadata_html.yml

title: Rake tutorial for beginners

author: ToshioCP

date: August 7, 2022metadata_pdf.yml

title: Rake tutorial for beginners

author: ToshioCP

date: August 7, 2022

documentclass: article

geometry: margin=2.4cm

toc: true

numbersections: true

secnumdepth: 2Delete the metadata from sec1.md. Please make sure that

the heading of “sec1.md” is the ATX heading from “###” to “#####” (not

from “#” to “###”).

The new Rakefile for HTML and PDF is as follows.

require 'rake/clean'

sources = FileList["sec1.md", "sec2.md", "sec3.md", "sec4.md"]

sources_pdf = sources.pathmap("%{sec,sec_pdf}p")

task default: %w[html:build pdf:build]

namespace "html" do

task build: %w[docs/LearningRake.html docs/style.css]

file "docs/LearningRake.html" => %w[LearningRakee.md docs] do |t|

sh "pandoc -s --toc --metadata-file=metadata_html.yml -c style.css -o #{t.name} #{t.source}"

end

CLEAN << "LearningRake.md"

file "LearningRake.md" => sources do |t|

learning_rake = t.sources.inject("") {|s1, s2| s1 << File.read(s2) + "\n\n"}

File.write("LearningRake.md", learning_rake)

end

file "docs/style.css" => %w[style.css docs] do |t|

cp t.source, t.name

end

directory "docs"

CLOBBER << "docs"

end

namespace "pdf" do

task build: %w[LearningRake.pdf]

file "LearningRake.pdf" => "LearningRake_pdf.md" do |t|

sh "pandoc -s --pdf-engine lualatex --metadata-file=metadata_pdf.yml -o #{t.name} #{t.source}"

end

CLEAN << "LearningRake_pdf.md"

file "LearningRake_pdf.md" => sources_pdf do |t|

learning_rake = t.sources.inject("") {|s1, s2| s1 << File.read(s2) + "\n\n"}

File.write("LearningRake_pdf.md", learning_rake)

end

CLEAN.include sources_pdf

sources_pdf.each do |dst|

src = dst.sub(/_pdf/,"")

file dst => src do

s = File.read(src)

s = s.gsub(/^###/,"#").gsub(/^####/,"##").gsub(/^#####/,"###")

File.write(dst, s)

end

end

CLOBBER << "LearningRake.pdf"

endThe points are:

sources are changed. An intermediate

file such as “sec_pdf1.md” is created in the pdf namespace.

The glob pattern FileList["sec*.md"] possibly picks up such

intermediate files. Therefore, the each source file is specified in the

arguments of FileList[] method.--metadata-file= is given to Pandoc to

import metadata.gsub method is used instead of gsub!

for string substitution. Since the return values are different between

the both, it is better to use methods without exclamation. (Using

gsub! is prone to include bugs because it returns

nil when the replacement does not occur.)Defining tasks with the same name in different namespaces will not cause name conflicts. This works well especially for large projects.

Rake behaves as follows when it is given the arguments below.

rake => Creates both HTML and PDFrake html:build => Creates only HTMLrake pdf:build => Creates only PDFrake clean => Deletes intermediate filesrake clobber => Deletes all generated filesNamespaces are useful for a large Rakefiles and libraries. When Rakefile becomes very big, it is often split into two or more files. Usually, they are one main Rakefile and libraries. If you put a namespace to your library, you don’t need to worry about any clashes with the other files.

On the other hand, a small Rakefile can be fine without namespaces.

Namespaces are also useful for categorizing tasks. When you have a large number of tasks that are called from the command line, you should consider organizing them in namespaces. For example,

# Database related tasks

$ rake db:create

・・・・

# Post related tasks

$ rake post:new

・・・・This helps users remember commands easily.

Rake features that haven’t explained yet will be described here and next section. This section includes:

Multitask method and TestTask class are described in the next section.

You can pass arguments when launching a task from the command line. For example,

$ rake hello[James]The task name is hello and the argument is

James.

If you want to pass multiple arguments, separate them with commas.

$ rake hello[James,Kelly]Be careful that you can’t put spaces anywhere from the task name to the right bracket. This is because spaces have a special meaning on the command line. It is an argument delimiter.

rake hello[James,Kelly] => One argument

hello[James,Kelly] is passed to the command

rake. Rake analyzes it and recognizes that

hello is the task name and James and

Kelly are arguments to the task.rake hello[James, Kelly] => Two arguments

hello[James, and Kelly] are passed to the

command rake. Rake recognizes that

hello[James, is a task name because no closing bracket

exists. But, since Rakefile doesn’t have such task, rake issues an

error.If you want to put spaces in the argument, enclose it with double

quotes ("). For further information, refer to Bash

reference manual.

$ rake "hello[James Robinson, Kelly Baker]"Bash recognizes that the characters between two double quotes is one

argument. And Bash passes it to Rake as the first argument. Then, Rake

determines that hello is a task name. And that

James Robinson and Kelly Baker are two

arguments for the task.

On the other hand, a task definition in a Rakefile has parameters after the task name, separated by commas.

task :a, [:param1, :param2]This task a has parameters :param1 and

:param2. Parameter names are usually symbols, but strings

are also possible. If it has only one parameter, you don’t need to use

an array.

In the example above, there is no action in the task a,

so the arguments have no effect. Arguments take effect in an action.

The action (block) can have two parameters. The second parameter is an instance of TaskArguments class. The instance is initialized with the arguments given to the task.

task :hello, [:person1, :person2] do |t, args|

print "Hello, #{args.person1}.\n"

print "Hello, #{args.person2}.\n"

endBlock parameters are:

Suppose that the task is called from the command line like this:

# The current directory is example/example7

$ rake -f Rakefile1 hello[James,Kelly,David]

Hello James.

Hello Kelly.You may have noticed that there are more arguments than parameters. It is not an error even if the numbers don’t match like this.

Some instance methods of the TaskArguments class are shown below.

args[:person1] returns James.args.person1 returns James.args.to_a returns

["James", "Kelly", "David"].args.extras returns

["David"].args.to_hash returns

{:person1=>"James", :person2=>"Kelly"}.each method on the hash returned by

to_hash.[R] The parameter name is used as a method name in the example above. But it is not actually defined as a method. Rake uses the

method_missingmethod (BasicObject’s method) to return the value of the parameter if the method name is not defined. Therefore, it looks as if a parameter name method was executed.

You can also set parameters default values with the

with_defaults method.

task :hello, [:person1, :person2] do |t, args|

args.with_defaults person1: "Dad", person2: "Mom"

print "Hello, #{args.person1}.\n"

print "Hello, #{args.person2}.\n"

endThe default values are now Dad for person1

and Mom for person2.

$ rake -f Rakefile2 hello[James,Kelly,David]

Hello James.

Hello Kelly.

$rake -f Rakefile2 hello[,Kelly,David]

Hello Dad.

Hello Kelly.

$ rake -f Rakefile2 hello

Hello Dad.

Hello Mom.If you want to add prerequisites in the task definition, write

=> and the prerequisites following the parameter.

task :hello, [:person1, :person2] => [:prerequisite1, :prerequisite2] do |t, args|

・・・・

endPrerequisites prerequisite1 and

prerequisite2 are added to the task hello.

Arguments are inherited by the prerequisites, so if you set the parameters in it, it can get the arguments.

task :how, [:person1, :person2] => :hello do |t, args|

print "How are you, #{args.person1}?\n"

print "How are you, #{args.person2}?\n"

end

task :hello, [:person1, :person2] do |t, args|

print "Hello, #{args.person1}.\n"

print "Hello, #{args.person2}.\n"

endArguments given to the task how are also given to the

prerequisite hello.

$ rake -f Rakefile3 how[James,Kelly,David]

Hello James.

Hello Kelly.

How are you, James?

How are you, Kelly?The example above isn’t practical, but I think it is useful to understand Rakefile arguments.

In addition to arguments, environment variables can be used to pass values to Rake, but it is the old way. Rake didn’t support arguments prior to version 0.8.0. At that time, using environment variables was an alternative to arguments. There is no need to use environment variables as arguments in the later version.

You can add a description for a task. Use the desc

command and put it just before the target task. Or, add a description

with add_description method.

desc "Say hello."

task :hello do

print "Hello.\n"

end

Rake::Task[:hello].add_description "Greeting task."The description string is set to the task instance when the task is

defined. The description is displayed with rake -T or

rake -D.

$ rake -f Rakefile4 -T

rake hello # Say hello / Greeting task

$ rake -f Rakefile4 -D

rake hello

Say hello.

Greeting task.

$If a task doesn’t have description, it won’t be displayed. Only the tasks with descriptions are displayed. Descriptions should be attached to tasks that users invoke from the command line. For example, the following is the Rakefile in the previous section,

・・・・

desc "Creates both HTML and PDF files"

task default: %w[html:build pdf:build]

・・・・

namespace "html" do

desc "Create a HTML file"

task build: %w[docs/my first Rake.html docs/style.css]

・・・・

namespace "pdf" do

desc "Create a PDF file"

task build: %w[My First Rake.pdf]

・・・・You can see the task description from the command line.

# change the current directory to example/example6

$ rake -f Rakefile1 -T

rake clean # Remove any temporary products

rake clobber # Remove any generated files

rake default # creates both HTML and PDF files

rake html:build # create a HTML file

rake pdf:build # create a PDF fileWhen a user see the message above, they can know the task name to

give rake. You could say that the description is a comment

for users.

On the other hand, when the developer wants to leave a note about the

program, they should use Ruby comments (# ... ...).

The -T option only prints what fits on one line, while

the -D option prints the entire description. Users can add

a pattern to limit the tasks to display.

$ rake -f Rakefile1 -T '^c'

rake clean # Remove any temporary products

rake clobber # Remove any generated filesThe pattern is a Ruby RegExp literal without slashes (/), not a Glob pattern. Some characters, for example asterisk (*), are translated by Bash So, users should surround the pattern with single quotes (’).

The following options are for developers.

-AT => Show all defined tasks. Prerequisites that

are not defined in the Rakefile are not displayed.-P => show task dependencies-t or --trace => show all

backtraceIn particular, the -t or --trace options

are useful for development.

If the Rakefile is not found in the current directory, it searches

higher directories. For example, if the current directory is

a/b/c and the Rakefile is in a,

a/b/c => no. go up one

directorya/b => no. go up one

directorya => Yes. Read Rakefile and

execute. At this time, Rake’s current directory will be a

(not a/b/c).You can also specify a Rakefile with the -f option.

Rakefile is often written in one file, but in large-scale development, it can be divided into multiple files. In that case

.rake extension to the library Rakefile (the file

name does not have to be Rakefile)rakelib directory under the

top directory (the directory containing the Rakefile)There is no programmatic master-slave relationship between the Rakefile and the library, but the Rakefile in the top directory is called the “main Rakefile”.

A file goodby.rake is in the directory

example/example7/rakelib.

task :goodby, [:person1, :person2] do |t, args|

print "Good by, #{args.person1}.\n"

print "Good by, #{args.person2}.\n"

endThis file is a library Rakefile and the task goodby can

be called from the command line.

# current directory is example/example7

$ rake -f Rakefile1 goodby[James,Kelly]

Good by, James.

Good by, Kelly.“Multitask” here refers to a method name, not “multitask” in general.

The method multitask invokes prerequisites concurrently.

The prerequisites must not to affect each other, or bad error will

happen. Generally, it is faster to use multitask than

task because task invokes prerequisites

sequentially.

A program fre.rb, which counts each word in a text file,

is located at example/example8. The details of

fre.rb is left out here. This program scans the files given

as arguments, finds the frequency of occurrence of each word, and

displays the number of words and the top 10 words and the count. Here,

“word” means string separated by space characters (/\s/ =

[\t\r\n\f\v]).

$ ruby fre.rb ../../sec1.md

Number of words: 2030

Top 10 words

"the" => 106

"is" => 63

"a" => 57

"task" => 52

">" => 47

"```" => 37

"and" => 29

"in" => 28

"it" => 28

"to" => 27This shows that the total number of words is 2030 and the most

frequent occurrence word is “the”. Now, prepare two Rakefiles

Rakefile1 and Rakefile2.

Rakefile1

require 'rake/clean'

files = FileList["../../sec*.md"]

task default: files

files.each do |f|

task f do

sh "ruby fre.rb #{f} > #{f.pathmap('%f').ext('txt')}"

end

end

CLEAN.include files.pathmap('%f').ext('txt')This Rakefile1 calculates the word frequency of the

files from ../../sec1.md to ../../sec7.md and

writes the result to files.

Rakefile2 is the same except that the output file name

is different and the task method on line 5 is replaced with

the multitask method.

multitask default: filesThe multitask method processes tasks concurrently in

separate threads. It is expected to work faster than

Rakefile1. We will use Ruby’s Benchmark library to measure

each execution time to compare. The program bm.rb is as

follows.

require 'benchmark'

Benchmark.bm do |x|

x.report {system "rake -f Rakefile1 -q"}

x.report {system "rake -f Rakefile2 -q"}

endRefer to the Ruby documentation for further information about benchmark library.

Run “bm.rb”.

$ ruby bm.rb

user system total real

0.000179 0.000043 0.566276 ( 0.569218)

0.000130 0.000031 0.980284 ( 0.271294)The first row is the execution time when the tasks were invoked

sequentially (Rakefile1) and the second row is the one when the tasks

were invoked concurrently (Rakefile2). Both finishes in an instant, so

you may feel there is no difference. But Rakefile2 was two

times faster than Rakefile1 as the results above.

You can expect speed improvements in the multitask method if you organize your tasks well and avoid interference.

The final topic is TestTask class. The current Ruby standard test library is minitest. Information about minitest can be found on its homepage. The explanation of minitest is left out here. But I think that using minitest is not so difficult. If you use it a few times, you will get the hang of it.

Usually, test programs are collected in the test

directory. Put your Rakefile in the directory and you can run your tests

concurrently.

Since creating test programs here would be a pretty big work, I’ll leave it out and just explain Rakefile and TestTask here.

require "rake/testtask"

Rake::TestTask.new do |t|

t.libs << "test"

t.test_files = FileList['test/test*.rb']

t.verbose = true

endIn this example, it is assumed that the names of test files start with “test” such as “test_word_count.rb”.

rake/testtaskRake::TestTask.new.

TestTask class and Task class are different. But they have relationship.

When a TestTask instance is created, the same name Task instance is also

created. After the Rakefile is executed, the tasks will be invoked.t is the TestTask instance.t.libs is the list of directories added to $LOAD_PATH.

Its default is lib.test_files method explicitly defines the list of test

files to be included in a test. Each test file is a ruby program with

minitest. Make sure that the test files don’t have any conflicts. For

example, if your test programs read or write files, the clash tends to

happen.t.verbose=true will show information about the test.

The default is false.Run the test task from the command line. ( There’s no example in this tutorial.)

$ rake testRake is a powerful development tool, which controls programs and methods. Rake has FileTask, which is similar to Make’s task. But Rake is more powerful than Make. Such Rake features has been explained in this tutorial. Rake is really flexible so that you can apply it to many projects. Now what you do is just apply Rake to your project.

This tutorial itself also uses Rake to generate HTML from markdown. See the Rakefile in the repository. It is similar to the Rakefile in section 4.

Thank you for having read this tutorial.